- Home

- Loring, Jennifer

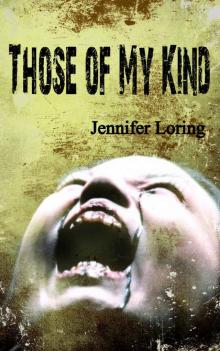

Those of My Kind Page 3

Those of My Kind Read online

Page 3

The tribe left her with their broken tools, scraps of discarded clothing, and the paintings of the Great Bear. On her first night without them, a white wolf with inscrutable blue eyes appeared at the mouth of the cave, as quiet and still as a life-sized totem. Instead of reaching for her spear, despite the full set of clothing she might have made from its copious fur, she knelt and bowed before it. It was not at all like the gray wolves her people had domesticated, as different from them as she was from her own people; too large, too ashen, too furry. But here was proof the rituals had not been in vain. The spirits had sent her a guardian.

The air is cool and dry during the day but turns much colder at night. Just before sunset, as the sky deepens into shades of red and purple, she and the wolf climb up into one of the caves. She makes a small fire and gathers her tools. Then she collects into a pile bones the bear that once lived here left, in case one of her tools breaks and forces her to make a new one. Though she carries a fishing net that holds most of her belongings, her striking platform proved too cumbersome to transport. Instead, she presses a small tree branch against the cave floor and scrapes away strips of wood with the hand ax.

She cannot make her weapon from stone. The pale limbs of a solitary tree reaching skyward in the valley tell her this, and she understands it though the language is not her own, though language itself is still beyond the comprehension of even the most intelligent of her species. The specter that haunts her is death, but the tree is life, and it is the one thing he fears—the reminder that he is a mere mimicry of a living thing.

Eyes that glow with a terrible and unquenchable rage flash in the darkness. Naked and feral, more animal than man, he squats at the cave’s mouth and taunts her with laughter, a bitter and sonorous sound like an ax striking against unformed stone. She finds something obscene in the way his tongue lolls from his mouth and he moves his hands over his belly. She pretends to ignore the evil spirit as she shapes the branch into a thick, short lance with a very sharp tip. She thinks instead about that day, ages ago, when she watched her band walk away from their encampment. They brandished their spears at her when she tried to follow, shrieking and shouting curses at her, warning her away. All she has left of them is a bracelet of beads and animal teeth her maternal grandmother made.

The wolf has abandoned her to hunt. She is, as always, alone again.

She whittles the spear with her large, strong hands, and sometimes she thinks about driving it through the shaman’s chest or into the heart of the mother that deserted her. When she glances up again, the man-thing is gone.

She moves deeper into the cave. With her hand ax, she cuts into her arm and lets the blood flow into a small stone bowl she uses to collect rainwater. The cut heals in moments. She mixes red ochre and sap into the blood then dips her finger into the substance and paints upon the cave wall. Her painting takes on the vague contours of a man and of herself standing over him.

The wolf returns and licks her wound, now a scratch. They curl up together behind the fire’s protective barrier, her face buried in the coarse ruff of fur at the wolf’s neck, her arm around its flank. The wolf does not sleep. It is always hunting, even while at rest.

He comes again the next night, as he has every night over her weeks of wandering through the valley. She is ready.

She smears stripes of red ochre upon her skin, then puts out the fire and waits outside the cave. The wolf has already run off into the darkness. The spirit’s strange eyes flicker about, his body moving faster than any human’s does. He hungers with the same hunger that seethes in her veins, but he will not debase himself to drink of animals. His eyes, black and fathomless as the night sky, tell her he could not conceive of it. But he does not have a man’s attachments. He is not a man; he merely wears the skin of one. He is an ancient spirit, one clever enough to have found its way into a human body.

A thought she does not wish to consider occurs to her then—for this terrible creature is, after all, her father—that perhaps he too experiences the crushing loneliness of a life separated from humanity. That, knowing nothing else, he makes others suffer with him. But she must harden herself against compassion, no matter how she might sympathize with his motivations. He does not belong in this world, for to live after death was an insult to the natural order of things.

The eyes stop moving. She has always been able to see well at night despite the valley’s vast and impenetrable darkness. The creature’s pale form crouches a short distance from her, mimicking her as he so often does. She clenches her fist around her weapon and pounces at him.

He is faster than she is and rolls out of the way. The tip of the stake plunges into the earth. Peals of laughter ring up from the valley as she yanks the wood free and scans the landscape. Neither her superior eyesight nor the pallid glow of the low-hanging moon reveals her quarry. There is only high yellow grass, disturbed by the occasional scrubby bush. And there is the tree, its branches gleaming like silver spears. A storm rumbles on the horizon. Flashes of lightning split the sky.

Behind her, the wolf lets out a plaintive howl. The beast was not there a moment ago. She begins to turn just as hands press hard into her back and shove, just as she realizes she has been deceived.

She tumbles over the edge, her fingers still gripping the stake. Bushes snag and tear at her hair as rocks batter and bruise her skin. She slams against the base of the tree as blinding pain flares in her spine. She can no longer feel her legs. She drags herself on her elbows a few centimeters from the tree so she can roll onto her back. Her hands are empty. Her gaze shifts downward. Blood slicks her belly, and from it protrudes the pale branch. She takes a long, laborious breath, conscious of the sting that gouges every part of her above her waist. She lies beside the tree, waiting for him to finish her. Instead, a huff of familiar, warm breath on her face, then a rough tongue, rouses her enough to open her eyes. The wolf stands over her, its muzzle wet and dark, still dripping blood. Her blood.

She grips the stake and wrenches it free, screaming as blood bursts forth from the wound and pain threatens to drown her. Gasping, she swivels onto her side. Blood, and the last of her strength, pulses out of her with each heartbeat. She raises the stake and summons all the energy she has left in order to propel it into the wolf’s chest. Viscous black blood bubbles up around the wood. The wolf transforms back into its man shape, black liquid spraying from his mouth as he sputters and coughs. His skin shrivels, blackens, and falls away. Then his skeleton disintegrates, leaving a damp, dark patch of earth where he had lain.

She tastes blood, so much of it welling up from the back of her throat that she begins to choke. She turns back toward the tree. She presses her hand against the trunk, and warm white light cocoons her. Rain spits down on her face, heralding a crack of thunder that shreds the night. A bright flash blinds her. The stench of burning flesh and hair replaces the rain’s clean scent as flames engulf both the tree and her body.

Her mind forms strange words she does not comprehend. It is the tree, she realizes, the revered ash that gives life but demands sacrifice. It understands her amorphous thoughts. It accepts her life as the ultimate ransom for her final wish.

If there are others like me, give them my power. Let my death give them purpose.

Fire strips away the body that caused her so much pain and separated her from her people. But it is only her body. Her spirit, still very much alive, is soaring above the valley, as light as the air that bore her aloft. She is free.

Chapter Four

Tristan tilted her head, her mind still reeling from the startling journey into humanity’s distant past. Her past. “But why are we called? There’s too much. We can’t possibly stop it all.”

No. And that was never our purpose, for without evil it is impossible to recognize good. But we cannot let the darkness prevail. We cannot succumb to our demon selves, though the temptation is great. Our power, given to wickedness, would be devastating.

“And I’ll die, won’t I? Like my aunt.”

<

br /> Because we are only half-human, each Hunter has the potential to live a very long life. But no Hunter ever has. The girl crouched down and with one finger drew something into the soft soil. A woman. A flame. I must leave you. Someone else wishes to speak with you.

Tristan zipped up her hoodie, though it did little to help against the night’s bitterness. The coldness came from within.

The pond, the trees, even Shapa, faded into black. When the world came back into view, its edges had grown soft and slightly out of focus as if viewed through an ancient camera. Shades of gray painted the trees. Tristan stood again on a dirt path but not the one in the park. Behind her lay a cluster of small houses, their windows dark and desolate, evincing no sign of life. Ahead of her, at the end of the road, squatted a crude hut with a dancing bear chained outside. The bear scrutinized her with too-human eyes, stood up on its hind legs, and pawed the air. Its breath condensed in a little white puff. A stove billowed out tangy wood smoke from somewhere within the settlement. The breeze that whisked across the path and into the starless night whispered of snow.

An eerie sense of coming home haunted Tristan, though she had never seen such a place before. She pulled open the hut’s wooden door and stepped inside.

A circle of candles lit the room, and in its center sat a woman, breasts bared in celebration of the upper body’s purity. Frizzy curls spilled down her back. Her eyelashes fluttered against her cheeks as she concentrated upon the images in her mind. She looks like me, Tristan thought and instantly grasped who it was.

A profound loneliness permeated the hut’s atmosphere. The woman had not made the choice to live there; others made it for her, and she accepted it without argument. She separated from her family for their own good.

She was i drabarni. The witch.

And she was Beebee Zsofika. The Hunter.

She did not open her eyes but raised her head and turned her face toward Tristan. “Jal told me you had arrived.”

“Jal?”

“My familiar. Surely you met him outside.”

“The bear?”

Zsofika smiled. “If that is what he appears to you.”

“You…know who I am?”

“Of course, penyáki. We are all a part of you. Our memories, our dreams, they are yours as well, as are those of all living Hunters. Claim your birthright, Tristan. My sister cannot keep you from it anymore.”

This was Mami’s daughter, all right. Zsofika waved Tristan to a spot on the floor across from her. Tristan sat down and crossed her legs.

“Why summon me now, after five years?”

“Because you are of age. Now that you are an adult, you will undergo the test proving your worth as a Hunter.”

“What’s going to happen to me?”

“The spirits can see the past and the present but not the future, because it is not yet written. I know only that it will exploit your weakness.”

Tristan repressed a frown. This was no help at all. “What happens to a Hunter who doesn’t pass the test?”

“Such a Hunter has no purpose, no place in this world. She is killed.”

“That’s a little harsh.”

“What would this Hunter do? She cannot live amongst humans. She does not belong to their world. How would she explain why she outlives everyone, why she never gets sick or hurt? A Hunter who cannot hunt has no other purpose.”

The logic was sound, if brutal. And not much comfort to a Hunter who hadn’t yet faced her test. “Mami said she saved your journals. I know she wouldn’t keep them in the house and risk Momma finding them. Do you know where they are?”

The flame hissed and sizzled in the dialect of the spirits. Zsofika, mute, watched and listened for a long time. Then:

“If I give you all the answers, you will have learned nothing. Everything is within you. Remember what my mother tried to teach you. The spirits are ready to speak, but you must learn to listen. You do not need my journals. You need to complete your training. You are very skilled with weapons, but there is another aspect of our combat you have neglected.”

“Magic.” Tristan sighed. She had no innate talent for it despite her strong Scorpio will. And magic had nothing on a well-placed explosive or a knife through the heart.

“It is a shame my sister turned her back on something so important to our people. But we can do nothing about that now. You must seek out another Hunter. There are very few with her natural affinity for magic. And without her, there is no hope.” Zsofika’s lips curved downward. She opened her eyes and analyzed the flame of a fat, black pillar candle. “She dreams of fire and blood. And she dreams of you, though she does not yet realize it.”

Fire and blood. The most sacred of elements. All the power of the divine resided in fire, for it not only destroyed but also healed and purified. This girl, whoever she was, must have some serious potential.

See, I tried to learn something about magic.

“It knows now that you exist. This will be her test.”

“What…knows?”

Zsofika studied the orange flame. The texture of the air had changed, had grown as brittle as an old woman’s bones, and brought with it a foreboding chill. Because it’s always winter here, Tristan thought. Because everything here is dead.

“She must face a Rém.”

The Terror. Tristan’s breath caught in her throat. “That’s Hungarian.”

“The one who pursues you is driven by an unimaginable rage. It cannot let go. It is the worst kind of monster, the kind that thinks it is doing what is right. In a sense, we fight for the same thing. A world that is pure.”

“Then why fight it at all? Why can’t we make peace?”

“There is no peace to be made with one who seeks destruction and death. It wants the end of this world and your power on its side. If it cannot have that power, it will stop at nothing to destroy what stands in its way. You mustn’t surrender to its lies. You must be willing to spill the blood of the corrupted.”

“Always.”

“Do not be so certain, penyáki. No matter how wise you have become and how much you have learned on your own.” Zsofika closed her eyes again, and a little sigh escaped her lips. “A Rém is the one who killed me. My weakness was my arrogance.”

Tristan rubbed her arms. Her breath condensed in spectral shapes. “Then why isn’t it my test? Why not let me avenge you?”

“That is exactly why it was not your test. A Rém is very old and very strong. If you were to go into battle blinded by vengeance, you would have surely fallen as I did.”

Minutes passed in awkward silence, and Tristan wondered if she should leave, though she did not know where to go or where she even was. Finally, Beebee Zsofika interrupted the quiet. “He was a good man, Tristan, before he died. What he became was not his fault. And I am sorry…”

For what? That she came too late to stop my conception?

But Zsofika never finished the sentence.

“So am I,” Tristan said.

The candle smoke grew thick enough to obscure Zsofika from her view. Her aunt dissipated into the fog, and the fog into the woods, and Tristan lay at the foot of the tree, staring up at the spot where the moon had been.

Chapter Five

Anasztaizia sat beside her father at the high table, on a stage beneath black scrim bunting and flags, with knights at long tables below them. Gazsi sat on Ispán Gergo’s other side. The trader, as their guest, should have sat with them, but she saw no sign of him. It was just as well; he’d unnerved her enough last night. The rest of Bodi filled the hall at crude trestle tables hastily assembled by carpenters hired from the village. Everyone wore his or her best black, amongst the peasants little more than a simple dress or tunic. Anasztaizia scratched at the fabric of her mother’s dress and fiddled with the absurd rings on her fingers as Gazsi introduced the feast with a prayer.

At its conclusion, the well-trained kitchen staff carried out bowls of fruit. Day-old bread plates marked each table setting, along with the knives

, spoons, and drinking vessels shared amongst the feasters. Salt pots and jugs full of ale awaited the inevitable slip of etiquette, the child or the half-wit who would forget to clean his mouth before drinking, or dip his bread into the salt pot. Anasztaizia made a game of it, picking out which villagers she thought most likely to end up pouring a new vessel of ale.

“You will eat something,” Ispán Gergo whispered in her ear. He leaned over like a lover, his breath on her neck like dragon fire. Gazsi had encouraged her to partake in the feast, for not doing so would arouse the ispán’s suspicions. She considered pretending to take ill, but it might provoke him all the same.

“There is so much food, Father. Let me wait until the second course.”

“Very well. But you must drink, at least.” He sipped the ale and pushed the jug toward her. A thread of liquid left behind by his lips clung to the rim. Anasztaizia’s gorge rose but she smiled politely and, turning it, lifted the vessel. The ispán leered at her, and his mouth opened a little in some private ecstasy. “That’s a good girl.”

The arrival of steaming pots of soup; dishes of salmon, herring, and eels; and vegetables provided a momentary escape from the ispán’s attentions. Anasztaizia wished for the dances and singing to begin, or even for the trader to appear and take his seat, so that each morsel of food she tucked into her mouth ceased to become an act of obscenity under her father’s indecorous stare. But no one dared say anything to him, not here. Not now.

At last, a minstrel, and high aristocracy from his manner. He plucked at a lute as he sang of Lady Katina’s beauty and kindness, and of the loss the castle district experienced in her passing. Ispán Gergo dabbed at his eyes. His nose became inflamed, a sweet potato affixed to his face, though Anasztaizia was uncertain whether crying or the copious amounts of ale he’d gulped had caused it.

The minstrel bowed deeply. “My sincerest condolences for your loss, Your Grace. Our world has grown darker without her in it.”

“That it has. Play another song, boy. You’ve a fine voice.”

Those of My Kind

Those of My Kind